red planet. its first 4k video was released couple of days ago on youtube.

-

mars

-

apple (fruit)

an edible fruit produced by apple trees (malus domestica). there are over 7,500 different types of apples known today with more and more being bred as time goes on. apples, like other crops and even animals, are bred for specific taste, purpose, and even appearance. apple trees originated in china and today, china remains the leading producer of apples.

-

the darkling thrush

1900 poem by thomas hardy. originally titled ‘by the century’s deathbed,’ the haunting piece describes the changes the narrator has observed through the turn of the 20th century. intriguing piece for many english majors as it contains strong pulls to both romanticism and modernism, and is deeply layered with opposing ideas which are interwoven. read it here

-

gobekli tepe

archaeological site in turkey’s anatolia region. consisting of around 200 pillars arranged into 20 circles and dating back to 10,000-8,800 bce. its true functions have baffled archaeologists since its 1963 debut into the files of researchers from istanbul university and university of chicago.

-

users' favorite quotes

the pain of losing something precious – be it happiness or material wealth – can be forgotten over time. but our missed opportunities never leave us, and every time they come back to haunt us, we ache. or perhaps what haunts us is that nagging thought that things might have turned out differently. because without that thought, we would put it down to fate and accept it.

sabahattin ali -

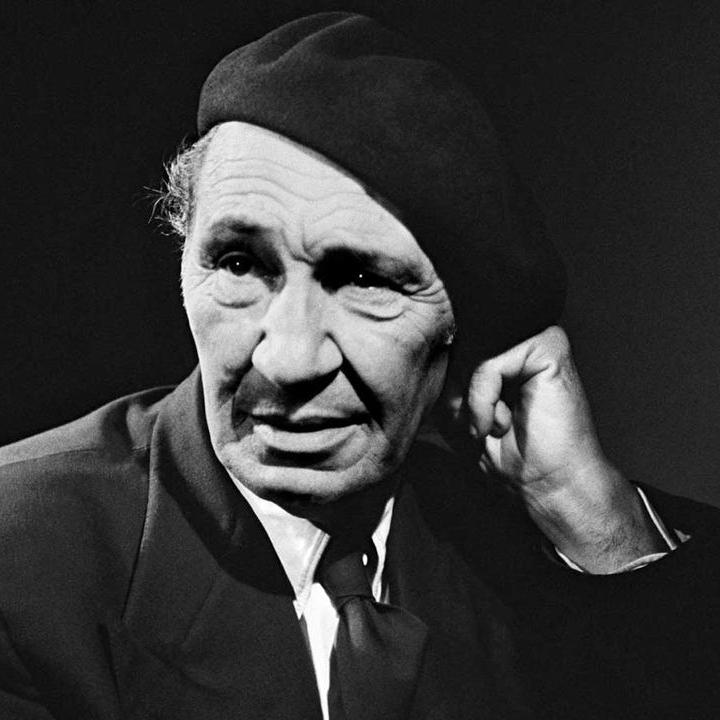

nusr-et

salt bae

-

turkey

a country where there is no culture of resignation.

-

thomas jefferson

the primary author of the declaration of independence was one of the most brilliant and versatile of the nation's founders. while best known as a political leader and writer, jefferson's curiosity carried him into many different roles: farmer, lawyer, scientist, inventor, architect, linguist, amateur musician, and founder of the library of congress.

his career in government was also varied diplomat, delegate to congress, and governor of virginia. after the government of the united states was established, he served as secretary of state, vice president, and served two terms as president, from 1801-1809. in spite of his achievements, jefferson was tormented throughout his life by his failure to find a solution to the contradiction of slavery existing in a free society. fearing financial ruin he freed only a few of his own slaves.

jefferson and his old friend—and former adversary-john adams both died on july 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the declaration of independence! -

american civil war

the world's first modern war.

-

state government reform

(see: #667)

-

users' confessions

love people so much if you want to lose them.

-

turkey

"you will be defeated by a camera on a tripod."

claims from an organized crime boss rock turkey's government -

alcetas

alcetas was a prominent macedonian warlord who was mentioned among alexander the great's influential generals. after alexander's death, alcetas was challenged by antigonus, one of alexander's commanders. the war between the two warlords took place in the region of psidia and resulted in alcetas' resounding defeat. alcetas sought refuge in termessos, and the residents of the city provided protection to him. in subsequent months, in order to protect the city from danger, the elders of termessos wanted to hand alcetas over to antigonus, who had set his military camp at the foot of the mountain. alcetas did not want to face a gruesome death, so he took his own life. to this day, his grave lies on a rock wall in the highlands of termessos.

the grave is a 15-minute trek from the colonnaded street of termessos. it is a pleasant hike, not a cumbersome one. the first thing i noticed upon reaching the site was the large rock carving of alcetas on a horse on the wall above the grave. it surprised me greatly to see that this rock carving survived despite harsh natural elements, such as the scorching heat and interminable humidity. image -

nusr-et

-

reddit

the world's biggest forum.

top 3 communities*:

1- r/funny 62m

2- r/askreddit 47m

3- r/gaming 42m